Presentation and Notes!

Start here, watch the slides and read the notes to learn about what makes a comic.

Lecture Notes:

Introduction: There are many different kinds of comics, which range widely in length (from comic strips in Sunday papers to graphic novels), style and genre (nonfiction to fiction, manga to superhero) and quality (professional to indy comix). (See McCloud pg. 4-5 for reference)

– What do they all have in common? Will Eisner (master comic artist, whose namesake is a prestigious award for comic-makers), called comics Sequential Art = two or more images in a sequence, or one after the other.

-“But isn’t film/animation a bunch of frames in sequence?” (McCloud, pg. 7)

-Yes, but those images occupy the same space, i.e. a screen. In comics, images are juxtaposed, or side-by-side, occupying separate spaces.

-“What about other forms of visual art and written word? Aren’t words side-by-side, or art hanging in a museum?” (McCloud, pg. 8)

– So, we need a better definition than simply juxtaposed sequential art.

– Comics Definition: Juxtaposed (adjacent) pictures or images, that can include text, which are deliberately (“on purpose”) arranged to convey information or tell a story. (paraphrased for age group, McCloud, pg. 9)

–Comics vs. Cartoons

– Single-Image pictures and words, like Family Circus or political cartoons, are not comics. While they share the same visual style, history and approach, they are cartoons. Comics = plural, multiple, or more than one images/pictures in a sequence.

– However, it is important to remember that these definitions of comic art do-not include subject matter or genre or style. From superheroes to lasagna-loving cats, comics can be anything as long as they fit this basic definition. They can even be non-fiction!

-Also, today’s digital comics have elements not even included in this definition. There is augmented reality, gifs in webcomics and some with other audio and visual elements. But, they still share the same basic principles.

Basic Elements of Comics

1) Language of Comics = how the message/story is told (reference, McCloud, pg. 24-36):

-Pictures: visual representations of a person, place, or thing.

-Words: or “copy” that can be in the form of sounds (onomatopoeia), dialogue/monologue (spoken word/conversations between 1-2 people), thoughts, narration etc.

-Icons: an image used to represent an idea. (ex: emojis)

2) Closure = the “grammar of comics” (reference, McCloud, pg. 62-67)

– If pictures, words and icons are the language, than closure is the grammar or structure of comics (i.e. how they are put together).

So, closure is to comics, as grammar is to how you write a sentence!

-Closure means observing the parts, but understanding the whole. Think of a photograph. Your senses and experience tells you that there is an entire world outside of the frame, even though you can see it.

-In comics, closure is achieved through panels, or one of several images or frames making up a comic.

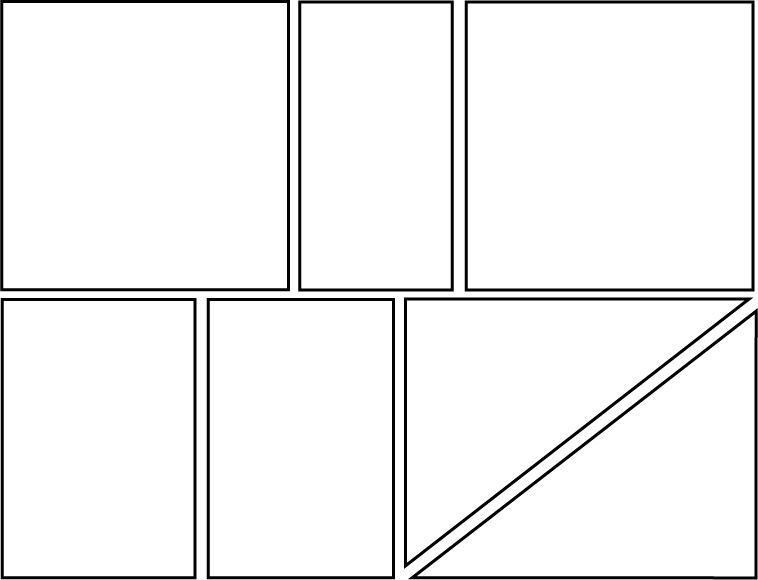

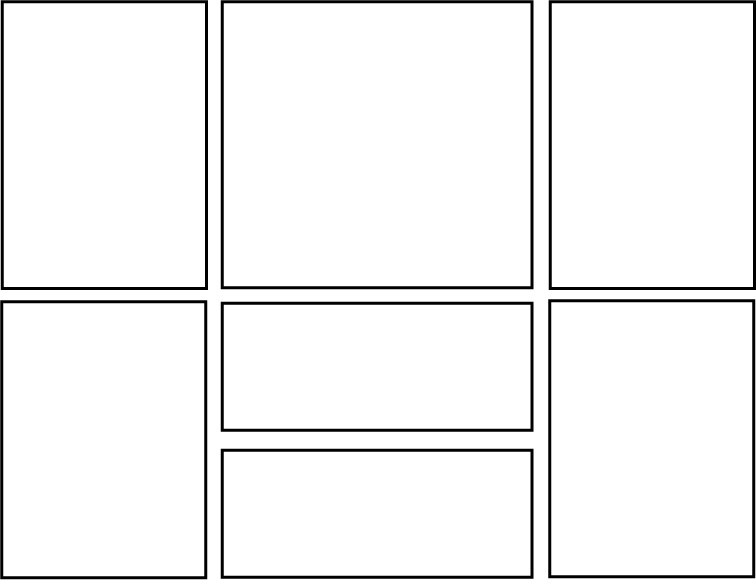

–Types of Panels (reference, McCloud, pg. 70-72)

Movement-to-movement– One action. This requires little closure or participation from the reader to imagine/understand the action.

Subject-to-subject– panels stay within the idea being pictured in a specific scene, but moves from one subject to another. This requires a little more reader imagination than movement-to-movement.

Scene-to-scene- large gaps in distances, space and/or time from panel-to-panel. Requires a good amount of imagination from the reader to understand what happens in between the panels.

Aspect-to-aspect- different aspects/perspectives within the same scene.

Non-sequitur- Latin for “it does not follow.” Panels show no logical connection and jump from seemingly unrelated images. This takes a great amount of reader imagination.

-While the most common panel types are action-to-action, subject-to-subject and scene-to-scene, there are no rules.

–Panels also come in all shapes and sizes, and how best to arrange them is up to the artist. In western comics panels are arranged top-down, left-right; in eastern comics (e.g. manga) panels are arranged right-left.

3) Frames– indicates time and space.

-Example (McCloud, pg. 95): Looking left to right (how we read), you can see a scene moving through time.

The panels indicate how time or space is divided. Think of them as scenes in a movie or play.

So, the size and shape of a panel can indicate the time and space of a specific scene. (In the example above, everything in the same setting or panel doesn’t all happen at once, but throughout a period of time. That is why the panel is long!)

4) Symbols– convey senses and emotions

– See McCloud pg. 131, 134 and 136 for examples.

There are many types of symbols, which can be in the form of images, pictures, icons and word bubbles, creative lettering and more.

Activity:

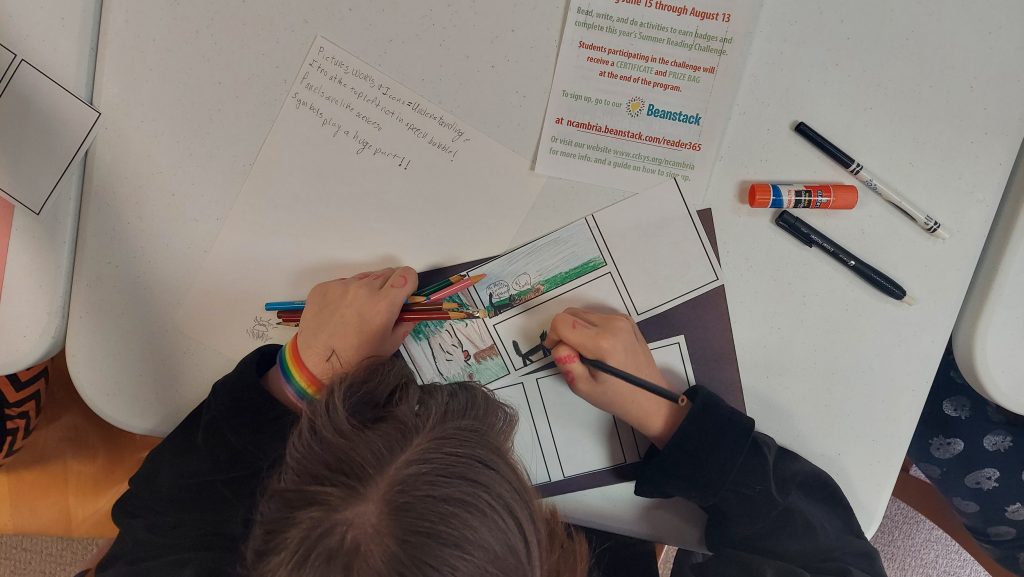

-The first part of the activity involves a quick brainstorming session. Using the brainstorming pages from “Look at My Book, ”students should be instructed to come up with a short narrative for a comic strip.

-After brainstorming, provide students with comic-strip templates and color pencils to create their own comic.

Supplies:

1) Projector/computer for PowerPoint presentation.

2) Pens and colored pencils.

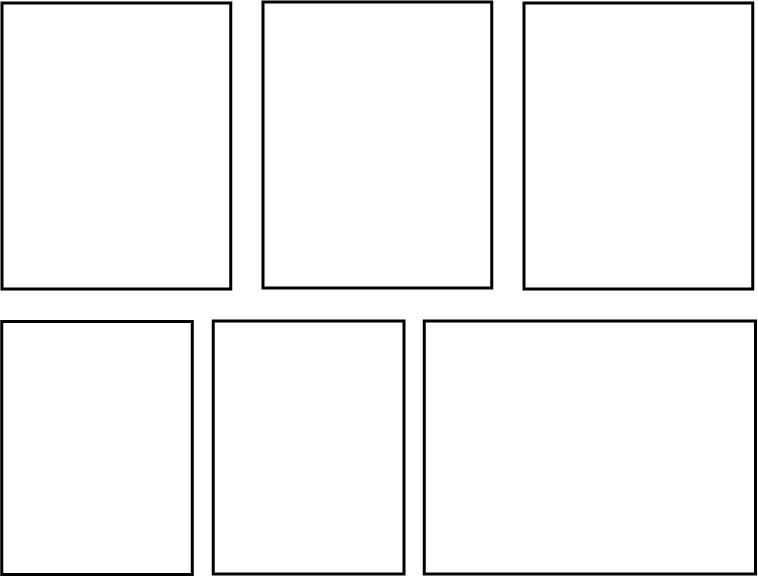

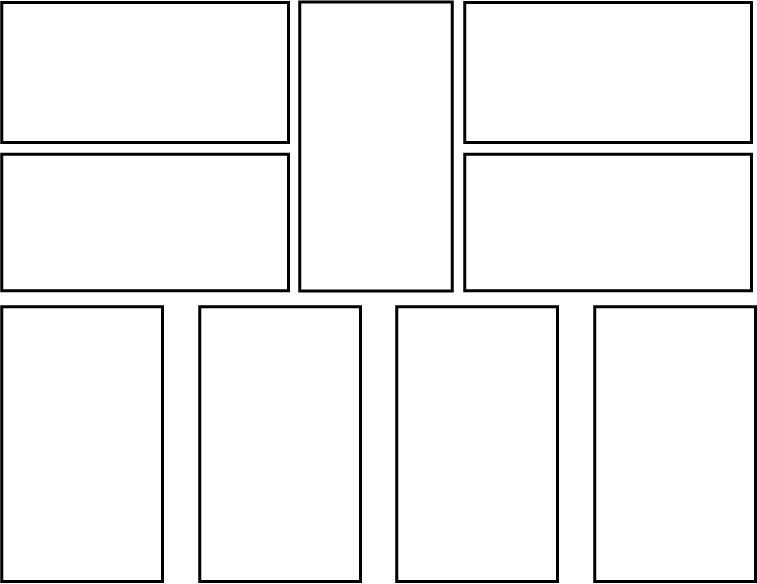

3) Comic-strip templates.

4) Scissors

5) Glue Sticks

Right Click to save and print out Images. Cut out the panels as you’d like, and make your own Comic Strips!

References

(NOTE- these are not available in our local collection, but can be ordered through Inter-Library Loan):

“Understanding Comics,” by Scott McCloud. Nonfiction, Graphic Novel.

“Look At My Book : How Kids Can Write & Illustrate Terrific Books,” by Loreen Leedy. Juvenile Nonfiction.

“The Great Women Superheroes,” by Trina Robbins

“Pretty in Ink: North American Women Cartoonists 1896-2013,” by Trina Robbins

“Drawing Words and Writing Pictures: A Definitive Course from Concept to Comic in 15 Lessons,” by Jessica Abel and Matt